North West America II

Description of work:

Photographic essay – Montana, USA 2005

Secondary Revision: Tracking the Dream – The work of Phil Taylor

Secondary Revision is the term used by Freud to describe the process through which we narrate our dreams. Our dreams themselves, as they are experienced in the moment of dreaming, have a phenomenal presence that is not yet articulated in words yet in narrating them, however formless and inconsequential the form that that narration might take, we begin to impose ourselves upon them. Our conscious minds enact an initial process of censorship upon the dream form, moulding it into a shape that can be articulated and shared, and betraying, even in that moment of articulation, the struggle between our unconscious desires and the conscious mind. The irony is that it is only through secondary revision that we gain access to the dream, as soon as we attempt to remember it, to re-think it, we change it and it slips from our grasp. The dream is thus always an elusive presence deflected through the prism of a language that destroys it at the very moment of articulation.

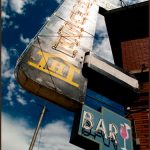

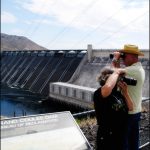

The work of Phil Taylor shares something of the structure of this process of secondary revision if only because the subject matter that he deals with is itself a kind of collective imaginary dreamworld. All his work, whether located in the touristic dream heavens of the British seaside town, the dislocated histories of Berlin, the immigrant gateway of the ports of Marseilles, or the desolate ex-mining towns of Western America, engages with the relationship between the impoverished reality of the lived environment and the fantasies that hold it in place. The town of Butte, USA, originating in the nineteenth century as a copper mining town and now a mere shadow of its former self, is haunted by its lost history, and by the memories of a mythical frontier way of life centred around the freedom of the individual and a disrespect for the federal state. The wild expanses of the landscape stand as a symbol for a masculine identity that finds its apogee in the figure of the cowboy and hunter, spending his days out on plains and mountains, driving some beat-up truck across the highways, and spending his nights drinking and gambling in the bars of the town.

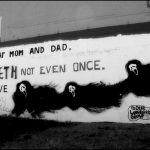

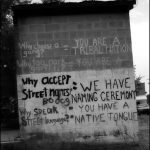

Taylor too is like a hunter, tracking the images that can tell this story as he travels through the state. Or maybe like a psychoanalyst tracking the deep circuits of the dream. His photographs have a fluid quality to them, as though grasped when moving, slightly off balance, evoking something perhaps remembered rather than seen. With his hallucinatory portrayal of livid pools of light against dark shadows he suggests the emergence of moments of illumination from the depths of the unconscious. Images recur with the insistence of memory: guns, bones, skulls, beat up trucks and store signs, a stuffed buffalo head, the same head as a tattoo on someone’s arm. An angel bestrides a dinosaur inside the empty hole of a skull, bones decorate the edge of a shack roof in a display of macabre decoration, bars lie empty and expectant, a lamp decorated with a stripper sits on a bedside table. Everywhere there are signs – “How to Handle Failure” says the sign outside the Cavalry Baptist Church, “Loaves and Fishes” on a store wall, “Blessed is he who should not be offended in me” says another sign – religion is everywhere, but revealed in fragmentary enigmatic phrases inscribed on the stage set of the town. The iconography is a familiar one – there are echoes of the uses of vernacular imagery by Walker Evans, of the ways in which he encoded an American identity in the very surfaces of the clapboard buildings, advertising hoardings, and streets of nineteen thirties. But Taylor reworks this imagery through the medium of the photo essay into something densely re-imagined. Many of the same images reappear in his moving image work, reassembled into timed projection pieces that reinsert the images into narratives, overlain by music and sounds.

Taylor’s work is dominated by the process of montage, by the chance juxtaposition of images, old photographs, graphic signs, and sounds. If he is drawn in his photography to the serendipitous, to the strange encounters between objects and people and signs, then he overlays this with other chance encounters, revising the story, telling the structure of one dream through another. In another work Gridlock he montages together all the images taken in his visits to motel rooms, the random arbitrariness of the structure yielding its own stories. Sometimes in his moving image work he will also create a grid of screens, as in Poisonville, a portrait of the desolation of Butte. Sometimes, as in La Marseillaise, smaller screens will appear inserted into the main one and we read them both through and against each other. In all this work the space occupied by the image is one that is multi-layered and open, suggesting an endless network of potential associations and readings.

It is in this fluidity offered by the convergences of new media technologies that Taylor finds his role as an artist exploring the collective subconscious. In a new work based upon a European rather than an American journey, Losing Ground, a digital video is shot through the windows of the revolving restaurant at the top of the TV tower in East Berlin. Time is speeded up and the windows themselves pass before our eyes with the regularity of a filmstrip. Outside the window weather moves across the city, twilight falls and the lights of the passing traffic zoom with alarming speed like meteors across the frame. The city has its own stories but Taylor retells them again, reworking them through the very medium of the screen, a kind of secondary revision, exposing the structure of the city dream.

Joanna Lowry • October 2011